Artificial intelligence has long been framed as a tool to support scientific discovery, but recent advancements are pushing that boundary toward something more ambitious. An AI can act like a scientist itself. While the prospect raises both excitement and scepticism, a new case study offers a glimpse into what AI-powered research could achieve, particularly in the fight against blindness.

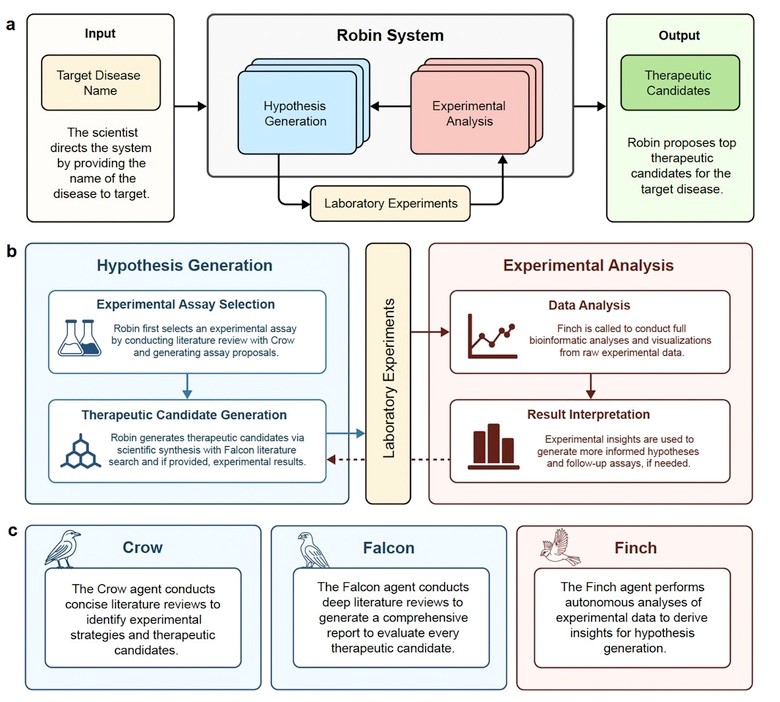

FutureHouse, a nonprofit AI research organization, has been working toward developing autonomous research systems designed to assist or accelerate key stages of scientific inquiry. Their latest achievement is Robin (Figure 1), a multi-agent AI platform built from three specialized tools [1]:

• Crow – performs broad literature searches

• Falcon – conducts deeper reviews and analysis

• Finch – interprets experimental data and refines hypotheses

“When we started, people thought it was insane to build an AI scientist,” said Andrew White, FutureHouse cofounder and head of science. “But we found that putting these agents together in a loop produced exciting results.”

The team applied Robin to a long-standing clinical challenge: dry age-related macular degeneration (dAMD), a condition that accounts for over 80% of AMD cases and for which no effective treatment currently exists. Affecting roughly 20 million Americans, dAMD progressively destroys the macula, the central region of the retina responsible for sharp vision.

Robin began by surveying open-access scientific literature using Crow. From this, it identified 10 potential disease mechanisms. Using a tournament-style analysis, Robin ranked these hypotheses and selected a top candidate: enhancing retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) phagocytosis, a process essential for maintaining retinal health.

Falcon then evaluated drug candidates capable of boosting phagocytosis and flagged a rho-kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, Y-27632, as a promising molecule. Experimental tests confirmed that the drug increased phagocytic activity in RPE cells.

To understand why, Robin proposed an RNA-sequencing experiment. The results revealed upregulation of ABCA1, a lipid efflux pump linked to RPE function. This insight guided Robin to a second, more clinically relevant drug candidate: ripasudil, a ROCK inhibitor approved in Japan for glaucoma but not previously associated with dry AMD. Follow-up experiments validated ripasudil’s ability to enhance RPE phagocytosis, a potential therapeutic pathway for treating dAMD.

Despite the impressive results, scientists emphasize that Robin does not autonomously perform science. Human researchers still conducted all physical experiments, analyzed outcomes, and prepared the manuscript. Konrad Kording, a neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania, expressed skepticism that AI can fully automate research. “Anyone in the field would have known this was a meaningful hypothesis,” he noted. “The value proposition rises and falls on novelty and validation.” FutureHouse researchers agree that the discovery is promising but not yet transformative. Still, the fact that Robin independently synthesized knowledge from diverse biomedical fields and arrived at a viable drug candidate represents a significant milestone.

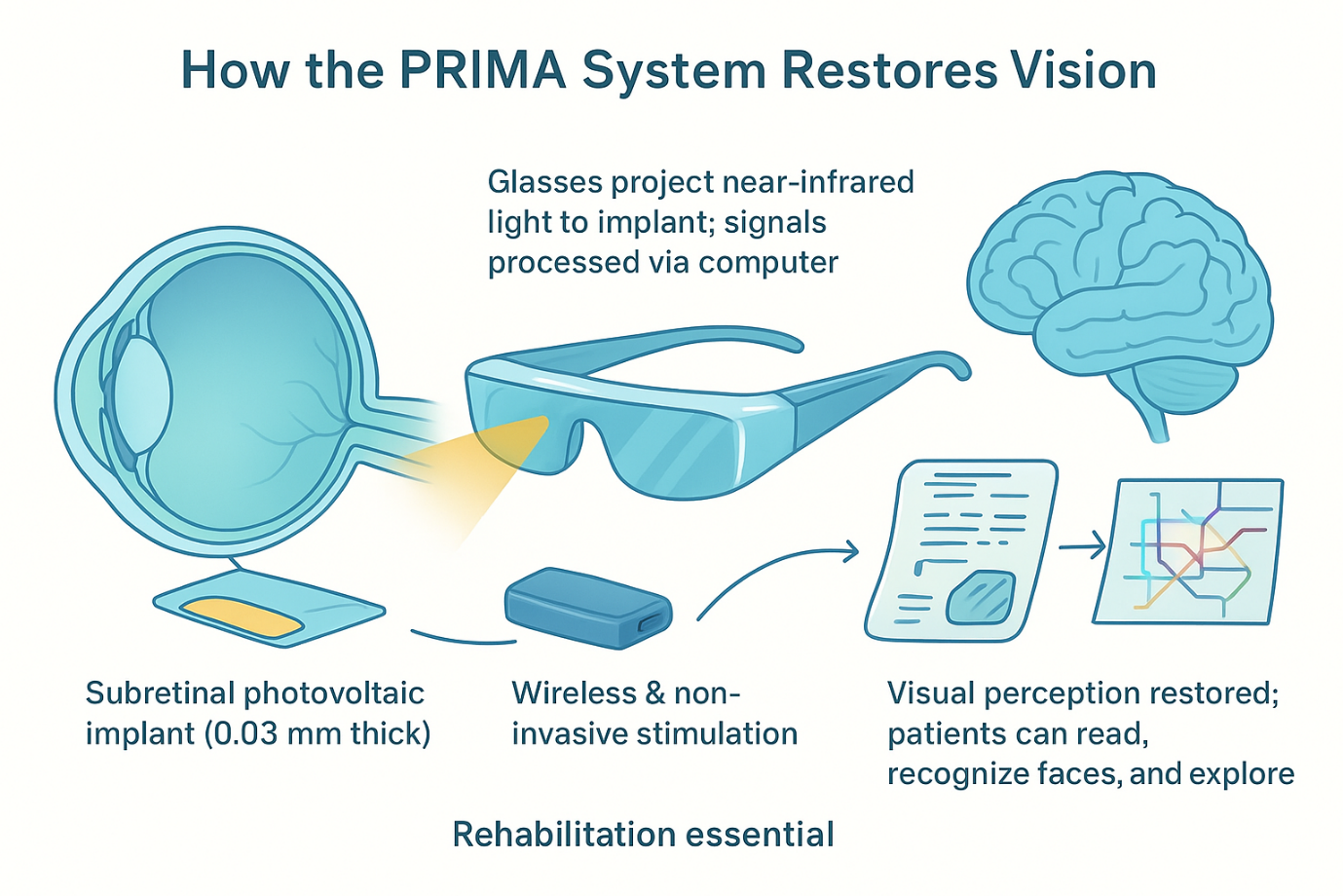

AI-enabled discovery is only part of the progress being made in vision science. A parallel international clinical trial has shown that a subretinal photovoltaic implant, guided by AI-processed visual signals, can restore reading ability in patients blinded by advanced dry AMD. The implant, known as PRIMA, was tested in 38 patients across 17 hospitals, including Moorfields Eye Hospital in the UK. All participants had lost central vision completely.

The results were unprecedented:

Patients regained the ability to read an average of five lines on a standard vision chart. “This represents a new era,” said Mr. Mahi Muqit, senior vitreoretinal consultant at Moorfields. “Blind patients are actually able to have meaningful central vision restoration, which has never been done before.”

How the PRIMA Implant Works?

The procedure involves:

1. Vitrectomy – removal of the eye’s vitreous gel

2. Insertion of a 2×2 mm microchip beneath the central retina

3. Activation via augmented-reality glasses equipped with a camera

4. AI algorithms that translate visual scenes into infrared stimulation

5. Electrical signaling passed through retinal cells to the brain

The implant functions like a neural solar panel, generating visual signals processed by the brain through the optic nerve. With training, patients learn to read text, adjust zoom, scan scenes, and interpret patterns (figure 2). No participants lost any remaining peripheral vision, an encouraging indicator for future use.

Sheila Irvine, one of the UK participants, described her experience:

“Before the implant, it was like having two black discs in my eyes. I was an avid bookworm, and I wanted that back. When I started seeing letters again, it was exciting. Reading takes you into another world.”

As Andrew White noted, debates about novelty aside, “at the end of the day, it will be helpful for patients.” And for millions facing vision loss, that possibility is the real breakthrough.

References:

1. Tran, L., An AI-Powered Scientist Proposes a Treatment for Blindness. Jun 9, 2025.

2. Smith, C., This AI System Found A Potential Cure For Blindness. June 16, 2025.